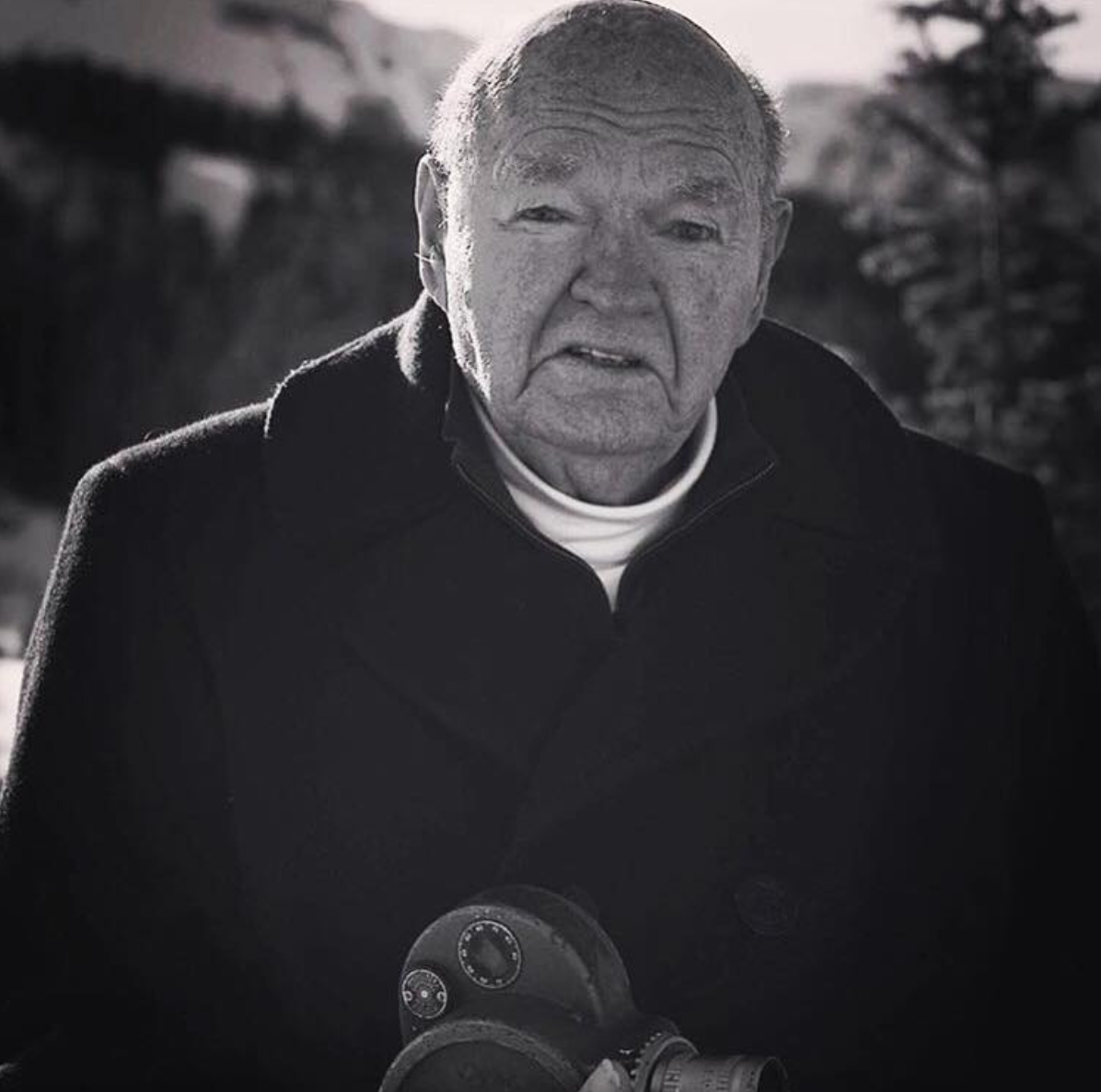

It is with great sadness that we announce that Warren Miller passed away Wednesday at his home on Orcas Island, he was 93. Warren was the pioneering ski filmmaker whose infectious zeal for the “pure freedom” associated with skiing, snowboarding and other pursuits inspired multiple generations of adventure-seekers around the globe.

Kurt Miller comments on his father’s life, “He lived an amazing life. From surfing on the beaches in Southern CA, sailboat racing in San Diego, Long Beach, San Francisco to Sydney Australia. Sharing with millions footage of skiers and riders sliding down the side of mountains from every mountaintop imaginable around the world. I thought you would enjoy the following short film in his honor.

A quick-witted, self-taught filmmaker who first filmed his own scenes for an annual self-narrated ski movie shown in small venues, Warren produced more than 500 adventure-sport films. His name, carried forward in a sports-media company, Warren Miller Entertainment, from which he was disassociated in his later years, became synonymous with snow sports across North America.

To his legions of fans, Warren’s annual ski flick amounted to cinematic manna from heaven — an overdue shot of cold air and deep snow to stoke the fires within winter warriors who had suffered through the long, hot months of snowless summer. The films, most of which began with jaw-dropping alpine-ski sequences, featuring top skiers and snowboarders delivered by helicopter to some knee-knocking heights and set to a pounding rock-music beat, never failed to produce hooting, shouting and delirium among the snow-deprived faithful. The pumped-up atmosphere, Warren said was like “showing a porno film on an aircraft carrier six days out of port.”

Those films’ first dulcet tones of Warren’s trademark voice — so distinctive that his wife, Laurie, forbade him from using it in ski-lift lines, just to avoid the fawning — usually were greeted with similar passion.

Warren’s ski films were equal parts travelogue, majestic cinematography and slapstick. Popular recurring comedic themes included scenes of piled-up bodies at the offramp for a beginners chairlift, set to campy music and ending with a lift attendant picking up some triple-jacketed rookie’s skis and poles and chucking them as far as they could be thrown. Warren’s trademark punchline — still repeated in some lift lines today: “Want your skis? Go get ’em!”

But as the years progressed through more than 60 annual films, Warren’s increasingly top-flight photographers went places no one else was going, filming scenes no one else captured. His productions in the 1980s and 1990s increasingly took viewers to exotic overseas locations, and featured “big air” jumpers such as Scot Schmidt, drawing concerns from some in the ski industry that the envelope was being pushed too far in terms of skier safety. His films included a world-class roster of skiing legends, including Otto Lang, Hannes Schneider, Stein Eriksen, Jimmie Heuga, Billy Kidd and Jean-Claude Killy.

Warren, at some turns, a vocal critic of increasing commercialization — and high prices — at major ski resorts, was known to spar with owners who chafed at his depictions of decidedly nonsales-material scenes such as long lift lines. Warren’s reply, in typical dry fashion: “If you don’t want pictures of lift lines, then don’t have lift lines.”

His films often were attended by parents and their children — sometimes even three generations of devotees to snow sports, who agreed that winter had not begun until they’d seen Warren Miller’s latest. Willi Vogl, who worked closely with Warren for decades commented, “Warren was one of the wisest and most genuine people I have ever met, he changed my life. He helped so many people make a living doing what they love–skiing. His memories will forever shape my life.”

Taken as a whole, the films were no less than a celebration of the sport, which Warren advocated as a burst of “freedom” and escape from stressful lives for people of all ages. Every film came with a trademark Warren challenge to audience members to throw caution to the wind and strap on some boards before their knees reached their lifetime capacity of bends.

In a 2010 Warren suggested he would be pleased if that get-up-and-go mantra stood as his legacy.

“I really believe in my heart that that first turn you make on a pair of skis is your first taste of total freedom, the first time in your life that you could go anywhere that your adrenaline would let you go,” Warren said at age 86. “And I show that in my films. I didn’t preach it. But once you experience that freedom — I’d personally narrate that show over 100 times a year — and I came to the conclusion that man’s search for freedom is embedded in our genes. That’s what everybody wants.”

As he aged, Warren turned the cameras, then most of the production work, over to specialists in his company, which in 1989 was acquired by his son, Kurt, and partner Peter Speek. They sold the film company in 2001 to Time Inc.; it has changed hands several times. Warren’s involvement with the film company, which still produces an annual film, largely ended in 2004.

He continued in later years to introduce some showings of the films in person, particularly in favorite “home-turf” venues around the Puget Sound area. His last public appearances were in “An Evening With Warren Miller” lectures in Seattle in 2010.

In his later years, Warren served as director of skiing (“Whatever that is,” he liked to say) at the exclusive Yellowstone Club in Montana, where a lodge bears his name. He and his wife, Laurie, spent summers on Orcas Island, where Warren enjoyed boating, drawing, reminiscing and finishing his extensive autobiography and other projects in an office filled with shelves creaking under the weight of thick, three-ring binders, one bearing the label: “ONE LINERS.” As a sketch artist and writer, Warren also penned 1,200 newspaper and magazine columns and 11 books, many self-illustrated.

Warren lived a quiet life in retirement, but was no island recluse: When local kids expressed a need for a place to hang out and play, Warren and a neighbor, the late surf and sailing entrepreneur Hobie Alter, led a campaign to build a world-class skatepark on the island. They quietly got it done.

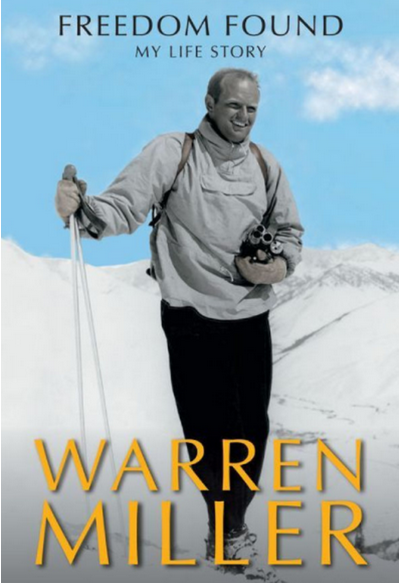

Born Oct. 15, 1924, in Hollywood, Calif., to Albert L. Miller and Helena H. Miller, Warren’s childhood was far from idyllic. The Great Depression derailed his father’s radio career, and Albert never worked again. The Miller family at times struggled to put food on the table and made periodic midnight moves to skip out on the rent, Warren recalled in “Freedom Found,” his 2016 autobiography.

“Rather than face the fact that my family was very strange, I made the assumption that the way our family lived was much the way that every family lived,” Warren wrote. “With hairdos for my sisters, whiskey for my father, and some food saved from dinner for me, my mother kept us together. A lot of people have had it a lot worse, but this was the way I had it.”

After a series of rudimentary jobs as a youngster, Warren sought refuge in the outdoors, bodysurfing off Topanga Canyon, hiking with Boy Scout friends in Yosemite, skiing at Mount Waterman, and surfing at San Onofre on a board built in a high-school shop class.

A seemingly natural entrepreneur, Warren purchased his first still camera at age 12, photographing fellow Boy Scouts and selling them prints. The business “marked only the beginning of what was to be a very, very expensive habit of documenting my world,” he recalled in “Freedom Found.”

Warren purchased his first skis and bamboo poles at age 15 for $2 — money earned delivering newspapers. He studied legendary Northwest ski instructor Otto Lange’s book, “Downhill Skiing,” before making his first turns in the San Gabriel Mountains in 1938.

“People remember their first day on skis because it comes as such a mental rush,” Warren wrote, echoing a refrain that would fuel his career. “When you come down the mountain from your first time on skis, you are a different person. I had just now experienced that feeling, if only for half a minute; it was step one in the direction I would follow the rest of my life.”

Warren attended the University of Southern California, playing varsity basketball and taking up speed skating before enrolling in the university’s ROTC program and serving on a submarine chaser in the U.S. Navy during World War II.

After the war, his attention shifted back to his first loves — skiing and filmmaking, which he documented using a Bell & Howell 8mm camera to film ski scenes while living in a teardrop trailer — famously existing on tomato soup made from hot water, ketchup packets and purloined oyster crackers — with ski pal Ward Baker in parking lots at Yosemite, Sun Valley, Jackson Hole, Aspen and Mammoth Mountain in 1946. The winter of their semi-discontent launched Mr. Miller’s lifetime reputation as America’s ultimate, responsibility-free ski bum — a term of sheer endearment to fans.

His antics even then drew the attention of a future long-term friend, Lang, then head of the Sun Valley ski school. “I knew of his existence, chasing down the mountain without a lift ticket, the lift attendant and the ski patrol in pursuit,” Lang told The Times in 1995. “Warren was … there’s a German word for it: lebenskuenstler — an artist in artful living, like an artful dodger.”

The first of what would become an annual Miller Miller ski film, “Deep and Light,” debuted in the winter of 1949-50 in Port Angeles (where Warren recalls pocketing a profit of $8); Seattle; and Vancouver. He spent the next three decades on the road 175 days a year, becoming the voice of skiing in America. He narrated his films in person while playing phonograph records for background music, often making up material on the fly.

“He has the touch,” said the late ski legend Lang, of West Seattle, who brought modern ski technique to the United States in the 1930s from his native Europe. Lang’s death in 2006 at the age of 98 was devastating to Warren, who saw it as the end of an era of classic skiing in the Northwest. Their admiration was mutual. “There isn’t a man who has contributed more to the joy of skiing,” Lang said of Warren.

Warren considered it all a labor of love. “I don’t think I’ve ever worked a day in my life,” he boasted in 2010.

Warren’s first wife, Jean, died of cancer at a young age. In 1957, he married Dorothy Roberts. The couple had a son and daughter, Kurt and Chris, joining son Scott from the first marriage. Warren would wed four other times, the last to the former Laurie Penketh Kaufmann, in 1988. The couple has lived on Orcas Island for 26 years.

Warren was inducted into the U.S. Ski Hall of Fame in 1978 and the Colorado Ski Hall of Fame in 1995. He was awarded Lifetime Achievement Awards from the International Skiing History Association in 2004 and from the California Ski Industry Association in 2008.

He later lamented not having taken courses in business development. “I was way beyond bankruptcy several times during my career, but too naive to know it,” Warren wrote of his own company. But it never diminished the rush he got from fans when he walked out on stage, particularly among audiences at venues in the West Coast, which welcomed Warren like a revered grandfather during his later years.

Warren is survived by wife Laurie; sons Scott and Kurt; daughter Chris Lucero; a stepson, Colin Kaufmann; and his three black dogs: Scotties Angus Bremner and Drummond McGregor and a huge Czech Shepherd, Bex. He was extremely grateful for his tireless caregiver, Ginger Moore.

Services are pending. Memorials may be made to the Warren Miller Performing Arts Center in Big Sky, Mont. Warren suggested that a fitting memorial, for those able, would be a run down a favorite local slope in his honor. (“If you don’t do it now, you’ll only be a year older when you do.”)

The record will show that the day Warren Miller died, the Pacific Northwest was receiving the most snow on Earth.

Source: Seattle Times