Scattered high on the craggy, snow-swept cliffs of the Caucasus Mountains, dozens of wide-mouthed metal pipes jut horizontally from the rocks. An elbow joint turns the pipes downward, like spouts of giant faucets.

Jean-Louis Tuaillon, Rosa Khutor’s mountain manager, was hired for his expertise in avalanche mitigation.

They are part of an intricate arsenal designed to protect Rosa Khutor, the new resort that will host Alpine skiing and snowboarding events at the 2014 Olympics in February, from the potentially catastrophic and deadly destruction of avalanches.

Rosa Khutor is so new — parts are still under construction — that there is little understanding of the likelihood and danger of snowslides. The first avalanche studies of the area were conducted in 2008, after Sochi was awarded the Olympics and just as construction of the resort began in earnest.

“It was totally virgin, a wild space consisting of large forests interrupted partly by avalanche tracks,” according to a 2012 paper written by outside consultants and officials of the flourishing ski area.

The experts found that conditions for avalanches were nearly perfect.

“Rosa Khutor is a challenging zone with many large and steep slopes,” the paper said. “This terrain is near the Black Sea and receives extreme precipitation that can lead to large and dangerous avalanche cycles.”

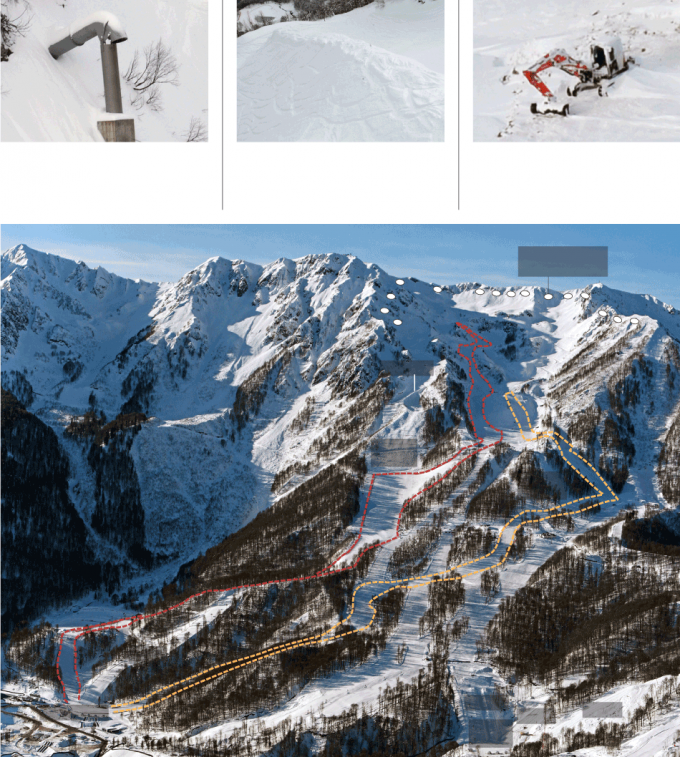

That is why there is a team of experts devoted solely to avalanche prevention at Rosa Khutor, some posted in a tucked-away office near the base and others stationed in a ridgeline cabin, above timberline, called “avalanche house.” That is why two backhoes crawl like giant insects atop the highest ridges, knocking away dangerous cornices before they topple. That is why mountainsides have been reshaped, with 30-foot-tall dams, to steer avalanches away from buildings, lifts, ski runs and people.

And that is why there are 43 huge pipes sprouting from the rocks, each of which can emit a remote-controlled explosive burst of oxygen and propane to create artificial avalanches before large-scale natural ones occur.

“With the philosophy of controlling them very often, we think we will not have a problem,” said Jean-Louis Tuaillon, Rosa Khutor’s mountain manager, hired largely for his expertise in avalanche mitigation at several western European resorts.

The top of Rosa Peak can feel like the ceiling of the world. In February, its jagged peak and those of its neighbors are meandering strings of white, like steppingstones of the gods. The elevation is 7,612 feet, hardly a majestic height. The Black Sea is visible on clear days, 30 miles to the south. Views compare favorably to most anything in the Alps or the Rockies. So does the snowpack.

About 1,000 vertical feet below the top, in a vast white bowl with no trees, is the planned start of the Olympic men’s downhill ski course. A bit farther down is where the women will start. Their separate courses twist down the mountain, over ridges and through steep ravines, into the trees and to a common finish area. Parts of the courses are in major avalanche zones. One massive berm, like an earth-made dam wall, is meant to protect the course from a major slide.

A decade ago, plans for Rosa Khutor included a few lifts and a modest resort. Everything changed in 2007, when Sochi was awarded the 2014 Games. The construction budget ballooned to $2 billion from $200 million, said Alexander Belokobylski, the executive director of Rosa Khutor. With 18 lifts and nearly 60 miles of ski trails, and plans for much more, Rosa Khutor is already the biggest ski area in Russia.

“We just built from scratch,” Belokobylski said. “The history of Rosa Khutor started in 2003. When Sochi got the bid, the whole project was expanded.”

But there was little historical weather data, which still causes concern about the elements at various venues during the Olympics. Sochi2014 organizers have taken drastic steps to ensure that there is enough snow, for example, by stashing massive mounds of last year’s snow deep in shady forests.

There was even less information about avalanche danger.

“There were not a lot of people in winter here,” Tuaillon said. “It’s different than the Alps. There were not chalets, no ski areas — or very few. There was not a lot of experience or information or data about avalanches. We make progress each winter. We never know everything, but we make progress each winter.”

As the resort was designed, avalanche studies were commissioned. The landscape was mapped in great detail, marked by avalanche zones — anything from a narrow gully to a broad plain that funnels dangerously downhill. The forests provided historical data, because young trees usually meant that an area was recently scoured by slides. They could show how far avalanches had traveled.

The icy cornices at Rosa Peak, if unmanaged, can rise three stories and threaten the ski area. Backhoes are used to topple the dangerous cornices.

Engineerisk, a French firm specializing in hazard studies and prevention, was hired to make recommendations. It found two major issues, both of which involved the planned Olympic ski courses.

“First, snow accumulations are particularly important along the wind-exposed ridgeline at the top of the resort,” Engineerisk’s Fanny Bourjaillat reported in a paper presented at the 2012 International Snow Science Workshop in Anchorage. “Notably in Rosa Bowl, these upper slopes directly threaten ski runs below. Depending on temperature, cold slab or heavy and wet snow avalanches can initiate almost everywhere and run into the ski area.”

The second issue involved an adjacent face of the ridge.

“Additionally, in Ober Khutor or East Bowl where many bowls overhang long steep slopes, huge avalanches are possible, entraining large snow volumes able to reach the lower altitudes,” the report said.

What followed was a vast avalanche mitigation project designed to combat worst-case scenarios. In February, one year before the Olympics, Tuaillon provided a tour. He stepped from an office at the base of the river valley, where there was no snow, and walked to the first of three gondolas necessary to reach the top of Rosa Peak, where the icy cornices, if left unchecked, can rise three stories and lean precariously over the ski area below.

The top of the first gondola is a busy area of lifts and lodges, all new, the primary base for skiers at Rosa Khutor. (Nearby is the Extreme Park, where Olympic snowboarding and freeskiing events will be held — out of range of avalanche danger, officials said.) Tuaillon led the way to an office, the hub of avalanche management. There were bunks for four people, a bathroom and a refrigerator. A detailed map covered one wall. Computers tracked weather and snow conditions — including snow temperature and water content — from a dozen places across the resort.

If the snow is determined to be too deep (usually eight inches or more) or too unstable near any of the 43 protruding pipes, part of a system called Gazex, a few mouse clicks can spark an explosion. An invisible burst of gas shoots down the spout. If things go to plan, snow below it cracks and slowly pours downhill. The growing mass can reach highway speeds. In some cases, it is steered from structures and chair lifts by large berms, like gutters of a storm drain. Eventually, the snow and debris settle harmlessly into a chunky pile.

Tuaillon and other avalanche experts long pleaded with Russian officials to let them use a fuller arsenal of mitigation techniques familiar to ski patrols at Western resorts — mainly, hand-tossed charges for specific trouble spots, and the Avalancheur, a cannonlike device that shoots charges into the mountainside from long range.

The Russians said no. They wanted no explosives in civilian areas, they explained, perhaps concerned about charges that did not detonate or large stashes of grenadelike bombs. Rosa Khutor sits just a few miles from the border with Georgia, and the Caucasus Mountains are home to anti-Russian extremists.

Last spring, after many demonstrations and much discussion, Tuaillon was told that he could use a specific type of charge (its two components, stored separately, are useless unless mixed) and one Avalancheur.

From the second gondola, Tuaillon pointed out the dams constructed during the summers to deflect snow in the winter. From the third gondola, rising beyond the trees and held aloft by towers growing straight out of rocks, the array of Gazex pipes was visible. Tuaillon pointed to the small cabin where four workers will serve as the eyes and ears of a mountain changing with every snowfall and shift in weather. And he showed the cornices at the top, heavy construction equipment clawing at danger’s edge.

“Honestly, I don’t think the danger is big,” Tuaillon said. “But like anywhere in the world, you can have crazy weather. And it is the mountains.”

By JOHN BRANCH

Source: NYTimes