By Warren Miller

Opening night for a new ski film has been a nervous, once-a-year deal for me for the last 54 years. There is always that question: will the audience like what I have just spent one year and $750,000 creating in order to entertain them for 90 minutes?

Opening night for a new ski film has been a nervous, once-a-year deal for me for the last 54 years. There is always that question: will the audience like what I have just spent one year and $750,000 creating in order to entertain them for 90 minutes?

Fifty-four years ago, I made my first feature-length ski film and every reason for opening night success or failure depended on me. It was 1949 and there were only 12 chairlifts in North America. I was teaching skiing at Squaw Valley six days a week. I did all of the photography while I earned my monthly ski instructor salary of $125. I shot every scene of the film, edited it, and borrowed $100 from each of four friends to buy a projector so I could show it. I even recorded the music that a girlfriend of mine played on her church organ.

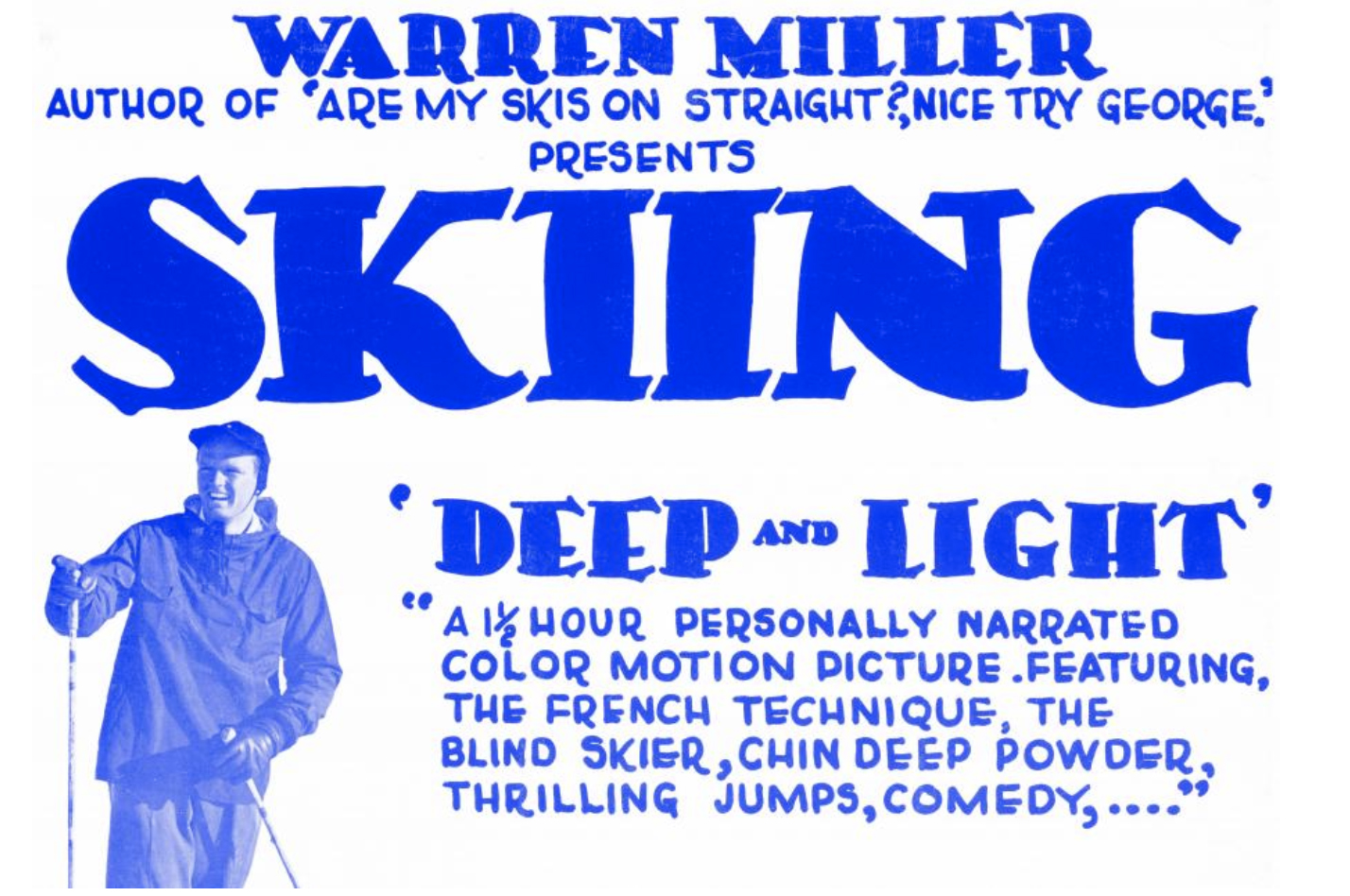

My first ski film, Deep And Light, was 16mm wide and 90 minutes long and cost almost $600 to produce. Our 2003 ski film is the same length and width and cost almost $750,000 to get onto the big screen. The cost has changed drastically and so has the whole experience.

In 1950, I was banging nails as an apprentice carpenter and living in my 1950 Chevy panel delivery truck. This was the same truck where I had edited the movie and recorded the church organ music.

On the day of the first commercial showing of my first ski movie, I had banged nails all day. After quitting time, I drove down to Santa Monica and took a free beach shower, as if I had been surfing all day. Then I climbed into my truck, shaved, changed into my tweed suit, tied my bow tie and drove across town to John Marshall Junior High School in Pasadena for the first commercial film show of my life.

I was nervous and astounded when I watched the Alpine Ski Club sell over 800 $1 tickets to that opening night show. I didn’t have a full 90 minutes of film, so I added a lecture about the revolutionary French ski technique to make the evening last long enough.

Before the start of the film, I rambled on about how I had taught skiing for Emile Allais at Squaw Valley and other stuff I had done before that. I told stories about living in the Sun Valley parking lot, shooting rabbits, poaching ducks, living on oyster crackers and ketchup for a winter. The stories served their purpose of eating up a lot of time. Apparently, some of the stories I told were so off the wall that the audience laughed themselves silly at their stupidity and at the fact that I had managed to survive the stories I was telling about myself.

The sponsors and I split that evening’s $800 profit and I received 40%. I had made one month’s carpenters wages in one evening. I earned $320, which was 80% of what I had spent to make the movie. Later, while driving to where I would park my truck and sleep for the night, I realized that I was onto something.

Three days later, I received a message from a Seattle ski club that had heard about my new film and wanted me to come show the film in Seattle. I figured that it would be a four-day drive each way on the then narrow, winding, two-lane road. In those days, I was making almost $90 a week banging nails, so in my phone conversation with the potential sponsor I said, “You realize that Seattle is a long drive from Los Angeles, so I have to have a $200 guarantee or 40% of the gross profit, whichever is higher.” They agreed and I kept that same financial arrangement with anyone who sponsored my films until I sold the company to my son almost 40 years later.

It took almost four days to drive to Seattle, where another 850 people bought tickets. In my first two shows, I grossed enough money to pay for the first feature-length ski movie I had ever produced. I was living in my truck and my only expense was my gas and food.

But I digress from my recent opening-night jitters. It happened here on Orcas Island last Saturday night, where we held a sneak preview of the film as a fundraiser for the Center for Performing Arts.

At the beginning of the movie, I made an announcement that all of the proceeds for the evening were going to the Orcas Center. I mentioned that I hoped the funds would be earmarked to buy the great new screen that the audience would be looking at all evening. At intermission, Mr. Hogan approached me and asked me how much the screen cost. When I told him that it cost about $2,000, he said, “I’ll buy it for you!” And he did. (Great things happen in a small town.)

It turns out that my jitters were unfounded. The audience laughed when they should have and reacted the way that our large production crew had planned. Despite my anxiety, the evening was a great success.

If history is any indicator, I’m sure I will be equally anxious next year. From those first two opening night shows in 1950, it has been downhill for me ever since. You know how it is every single time you shove off to ski or board downhill? You have butterflies! My butterflies have been around for 54 years.